By Anne O’Connor

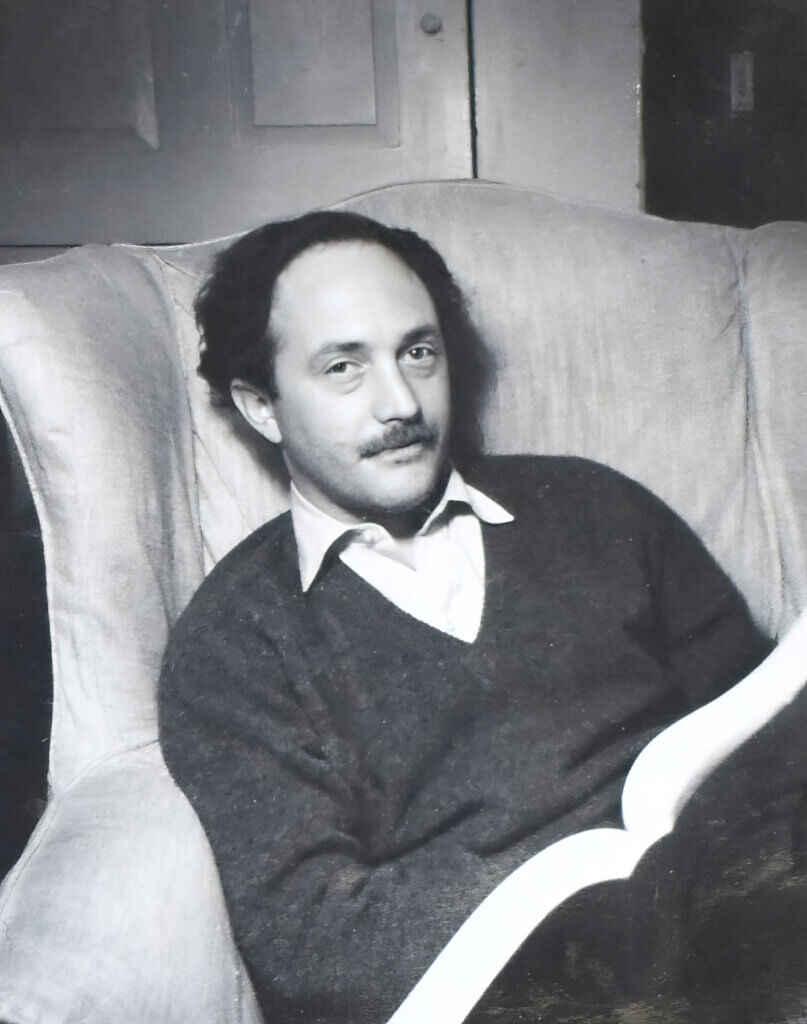

When Carl Velleca ran for selectman in 1976, Concord was in the spotlight, not for its part in the 200th anniversary of the American Revolution, but for a battle over prisoners’ right to vote in the town where they were imprisoned.

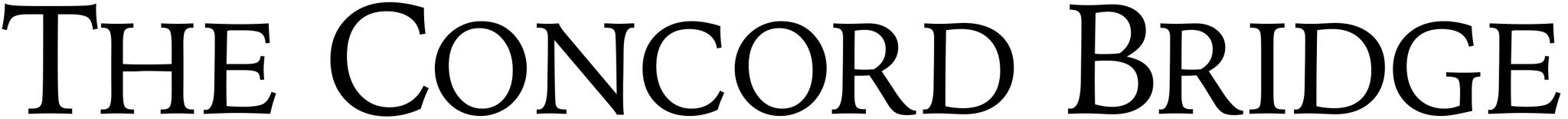

In early 1976, following state guidance, Concord’s Board of Registrars went into the prison to register the convicts who wanted to vote.

The town did some investigating before sending in the team. Then-Town Counsel Tom Swaim researched the legality of allowing prisoners to vote. He found that prisoners in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania were eligible to vote in the cities and towns where they were serving their sentences.

Today, states continue to debate prisoner voting rights and their ability to sway elections. The issue played out in dramatic fashion here nearly 50 years ago when Velleca, an inmate at MCI-Concord, ran for office.

Velleca, nicknamed “Bluejay,” was a career criminal and crime boss based in Lawrence, according to the Wilmington Town Crier. Originally incarcerated in Walpole, Velleca had been transferred to MCI-Concord, known locally as “The Reformatory.”

In town, some Concordians got behind his candidacy.

Phebe Ham, who became Concord’s 2023 Honored Citizen, ran Velleca’s campaign.

She told the New York Times in the days before the election, “I couldn’t help getting involved. First Blacks got the vote, then women, so it seems right that prisoners should have a say in politics, too.”

But others in town feared the inmates would vote as a bloc and could easily elect a fellow prisoner to the Board of Selectmen, Swaim said.

As town counsel, his tasks were completed at the behest of the town manager. Once he presented the research, his connection with the voting rights of Massachusetts prisoners ended. He said that as a young lawyer, at least at his level, the case “flitted” by.

Campaigning on furlough

The court got involved when Henry Dane, a local attorney, filed suit against allowing the prisoners to vote in a local election. State and national press agencies arrived in town. A bombing by an activist group delayed the superior court proceedings in Boston.

Dane, who went on years later to become chair of the Select Board, disagreed that allowing prisoners to vote in local elections was permitted under the law. After all, they were not voluntary residents in town.

The nation followed the case, with news broadcasts on ABC, NBC, and CBS in April 1976.

Local voters had a chance to meet Velleca at a buffet held by supporters at the Colonial Inn. But, according to a news article, more media than residents attended the event.

Velleca used furlough time to campaign. If elected, he planned to use work-release time to attend board meetings.

“Something like that was just out of order … [Filing the suit] had nothing to do with sympathy for people who were incarcerated,” Dane said.

Since prisoners are only temporary, involuntary residents of Concord, Dane maintained they should not vote in local elections in municipalities where prisons are located but in the places where they lived, by absentee ballot.

Their right to vote in state and federal elections was protected by the state Constitution, he said.

The lawyer requested the Board of Registrars go back to the prison and query the newly registered voters about their residencies by asking about the address on their driver’s license, where their children were in school, and “so on and so on,” Dane said.

The inmates did not cooperate on the advice of their lawyer.

An explosive case

Dane then filed suit in the state Supreme Judicial Court, which sent the case back to Suffolk Superior Court for a hearing.

Driving into Boston on the day of that hearing, Dane heard on the radio that a bomb went off in the courthouse, injuring 19 people.

Dane was not sure if the bomb was meant to send a message about the Concord case or about another case that day: that of Susan Saxe. The radical was on the FBI’s most wanted list, along with Katherine Ann Power, now a Concord resident, and others. They participated in a bank robbery that resulted in the death of a policeman.

A temporary injunction allowed the registered voters from the prison to take part, but their votes would be impounded until the court reached a decision.

In one of the largest turnouts for a local election, Velleca was soundly defeated, garnering 599 votes. The top two and winning candidates received 4,357 and 3,794, respectively.

Then and now

The state Supreme Judicial Court found in favor of Dane in 1978. Convicts and former inmates are legally entitled to vote in their home community, not in the city or town where they are imprisoned, unless they are residents or can prove intent to remain in the community.

In 2000, an amendment to the Massachusetts Constitution made it illegal for prisoners to vote.

As of 2023, only two states and Washington D.C. allow incarcerated people to vote. Others, including Massachusetts, restore the right to vote when their prison sentences, and sometimes parole, are complete. Ten states do not restore the right to vote automatically but may on a case-to-case basis, according to Ballotpedia.

Velleca, the inmate candidate who former Boston Globe columnist Mike Barnicle called “my expert on criminal justice,” was paroled and became a lay preacher.

He died in the pulpit of a Saugus Church in 1980.