His name is Hasan, but he prefers to be called “H.” He’s nine years old and likes shirts with collars, singing and dancing, jumping on trampolines and writing.

Hasan is also a mostly nonverbal boy with a diagnosis of autism.

But that is not what defines him.

What does define him, according to his mother: determination, resilience, creativity, and a sense of humor that shines through in his writing.

In November 2021, Hasan Ahmed moved with his family — mother Ishwarya Kumar, father Aseem Ahmed and sister Laiba Ahmed — from India to the United States, where they settled in Concord.

But it wasn’t until last May that Hasan’s family finally learned what makes him tick — and that is where Hasan’s story begins.

Hasan underwent different forms of therapy, from music to sports, after being diagnosed with autism while living in India, said Kumar.

“We’ve tried everything that helps him and enables his body,” she said.

For the longest time, the focus was on all the things Hasan could not do.

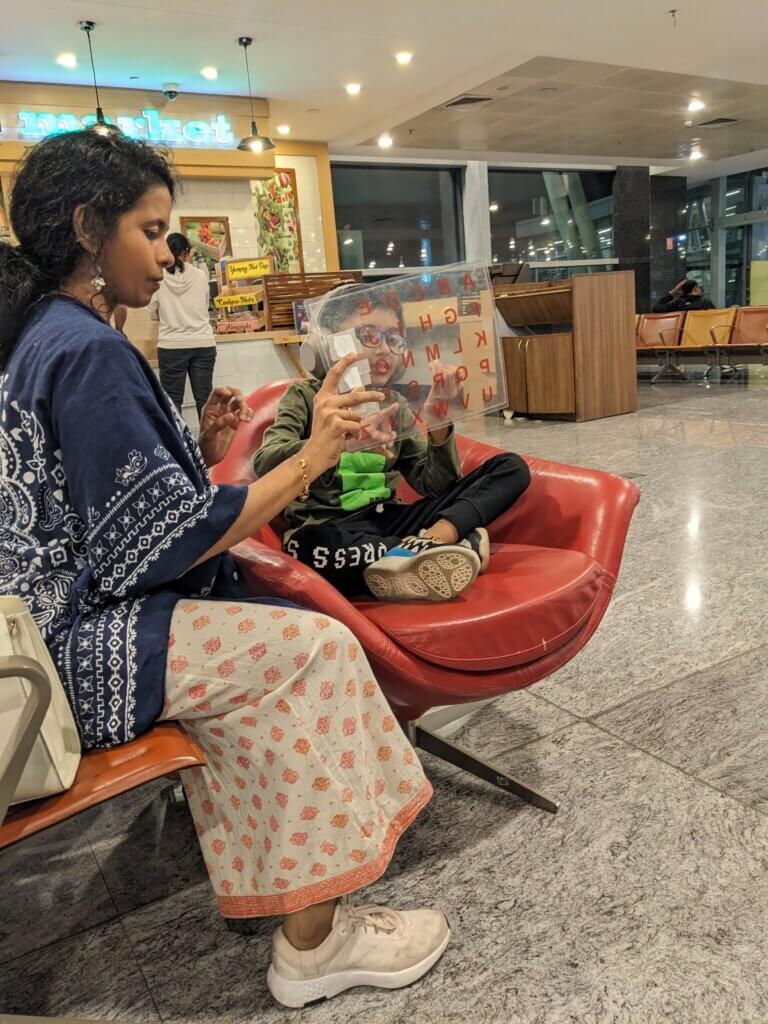

Then the family began to explore SOMA RPM. The “Rapid Prompt Method,” distributed by the nonprofit educational group HALO, teaches that while Hasan’s body may not always do what he wants it to do, he is still able to think and feel. It is a concept called “presuming competence.”

In a nutshell, “you presume competence in a child. You presume that they’ve been listening and they understand, no matter what their body tells us,” Kumar said.

Speech is difficult for Hasan because he cannot perform sophisticated motor skills, so he received a letter board. To everyone’s delight, he was able to point and poke and answer questions, one letter at a time.

“Initially, we thought he never knew letters, but turns out he’s been listening, seeing, looking — he’s been reading,” Kumar said.

They started by asking him simple, objective questions which have only one answer.

“It was a revelation, honestly, because the kind of things he knew [were] very age appropriate,” Kumar said. “Then I realized his body could be dysregulated, but he has a beautiful mind and we explored more and more and more and … the journey has been so full of greatness.”

Hasan’s skills at pointing out letters have improved so much he now uses a keyboard.

Becoming a published writer

When his parents asked Hasan to tell them about his world, his response was a poem titled “Welcome to My World” published last October 27 by Kind Theory, a Texas-based nonprofit that educates schools, employers, service providers, law enforcement and other organizations about neurodiversity, disability justice, and ways to understand and support people with autism and ADHD.

Hasan now has a one-year contract with Kind Theory and writes two to four stories a month that are published on their website.

“They would like to amplify the voices of neurodivergent children. So, they love his work, and they’ve been publishing his work,” said Kumar.

In his poem “Imagine,” Hasan invites the reader to swap their body with his. He describes his body, noting that his “eyes take me to a different planet” and how he “recently discovered that I can talk with my fingers.”

In “Questions I Have,” Hasan wonders how many Hasans are in the world and if birds and animals can communicate on a letter board.

He recently entered his first creative writing competition, sponsored by a family in the U.K. in memory of their son, Christopher Finn, who died in 2023 at the age of 21. The topic was “celebration.” The competition is only open to people who use a letterboard or keyboard to express themselves, like Finn.

Hasan opted to write a letter to Finn.

“He’s hilarious,” Kumar said. “He says in the letter, ‘I think you’re in a different planet, so I’ve decided I’m just a young lad portraying information to you from Earth.”

The entire letter outlines things to celebrate on Earth, said Kumar. “In my wildest dreams, I never would have thought of a letter format. He surprises me at every juncture.”

It took Hasan five days, writing for about 45 minutes a day, to finish the letter.

Writing helps regulate Hasan, Kumar said, bringing him “to a state of calmness.”

“I think it gives him some kind of ease,” she said.

Getting to know Hasan

For the first time, Kumar is getting to know her son, and there have been more than a few surprises along the way. She recently found out the shoes she has been buying for him are uncomfortable and he prefers shirts with collars.

“He’s been wearing uncomfortable shoes for eight years. He’s been wearing the kind of shoes he might not have liked. He’s been wearing clothes that I chose for him. He’s been doing things the world thought was right for him,” she said.

Come to find out, he loves Rowan Atkinson in Mr. Bean and likes to listen to podcasts and music. On occasion, he wears noise-cancelling headphones.

Hasan recently turned nine and surprised his parents by asking to celebrate with friends at a trampoline park. He made his own guest list and asked for a cake with geometric shapes.

“All of his life, we’ve been thinking he likes animals — he was always spouting out words of animals. But he told us they were just loops (words that get thrown out and don’t mean anything),” said Kumar.

“We’ve been proved wrong as parents in many of our assumptions, and that is a happy thing,” she added.

She encourages people to realize that although Hasan and others like him may have dysregulated bodies, it does not mean they cannot think, feel, or listen.

“They are — 100% of the time,” she said.

In Hasan’s words: “Next time you see me try trusting my words, not my body.”

To read more of Hasan’s poems, visit kindtheory.org. To read the family’s blog, visit facebook.com/ishwarya.kumar.85.