By Laurie O’Neill — Correspondent

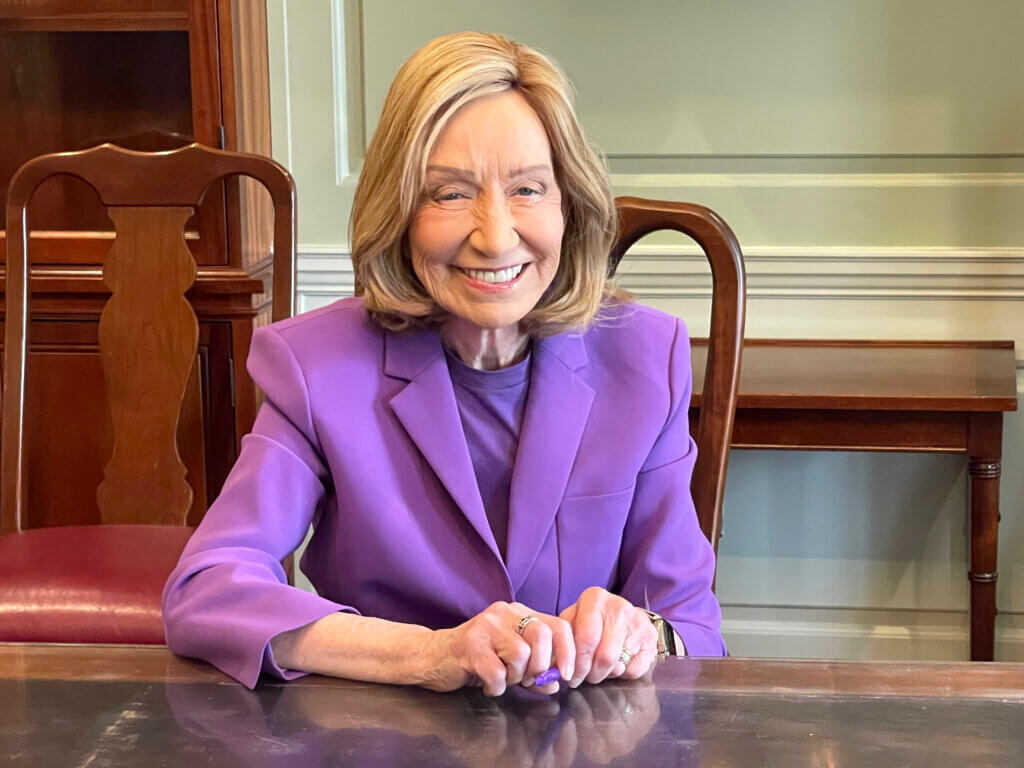

Petite, blond, and wearing a purple jacket and black pleated skirt, eminent American historian and Pulitzer Prize winner Doris Kearns Goodwin entered the Goodwin Forum of the Main Library last Sunday on the arm of her son, Michael, to the strains of a cello.

She smiled warmly, declaring, “Hurray!” while greeting her guests, many of them old friends. Then, speaking in her characteristic rapid style but lyrically, as if reciting poetry, Kearns Goodwin held rapt a crowd that spilled into the rotunda.

“I feel like I’m home today,” she said. “It means so much to me to be back in this town where Dick and I lived so happily and which I love so much.”

Kearns Goodwin, 81, was there to tell a love story, not only that of her and her late husband, acclaimed presidential advisor and speechwriter Dick Goodwin, but also their love story with America.

A project they undertook before Goodwin’s death from cancer six years ago, to examine the contents of 300 boxes of his letters, documents, photos, and papers, mostly from the 1960s and stored for decades, would lead to the book Kearns Goodwin completed.

“An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s,” a blend of memoir, biography, and history, was published this month.

A man of his times

Goodwin was, in a way, the Forrest Gump or Zelig of his era, finding himself as a young man not only in the room where it happened but also a major player in the event. He was a confidant of John F. Kennedy and assisted Jackie in planning his funeral, making sure an Eternal Flame burned at his gravesite. Goodwin was with Robert F. Kennedy when he died.

His professional life is unquestionably linked with that decade, a chaotic period marked by antiwar protests, the struggle for racial and economic justice, equal rights, and the assassinations of JFK, RFK, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Penning some of the most powerful political speeches of the 1960s, Goodwin helped design Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society.”

The Goodwins were married for 42 years and lived in Concord for most of them, raising three sons. A few years ago, she moved into a condo in Boston. The couple possessed some 10,000 books and had stored the boxes of memorabilia, but they had never looked at them. Goodwin had long felt it would be too painful — for one thing, he had left LBJ’s administration due to differences over the war.

But one summer morning, he suddenly decided it was time: He wanted to put his memories to paper.

Excavating the past

So began a sort of archaeological dig, during which the couple reminisced, reflected on, and debated those turbulent times while sorting through what they considered a time capsule of the decade. “It was the adventure of our lives,” Kearns Goodwin said.

Relating some of the more colorful highlights of his professional life, Kearns Goodwin included the time President Johnson summoned Dick and another advisor to the White House to discuss his vision of where the country should go after the Civil Rights Act. When they arrived, the men were told LBJ was in the pool. They found him there, swimming laps, naked.

“Come on in, boys,” said the president. The advisors shrugged, shed their clothes, and jumped in, and the three held onto the pool’s edge and outlined a plan.

Kearns Goodwin said it was hard to leave their Concord home but “painful” to stay. “I missed him so much,” she said of her husband, whom she described as “funny, warm, arrogant, and brash.”

She said she wondered if it would be “too sad for me to finish what Dick started.”

“But I did it,” she added with a smile. “I kept my promise to him.”