By Laurie O’Neill — Correspondent

Small leatherbound books of works by Austin, Wordsworth, and Hardy that date to the 1800s and early 1900s. Delicate china cups with whimsical painted words such as Remembrance. Vintage napkin rings —silver, wood, glass, or porcelain, some with cryptic monograms. All are small collections that this writer built over the years.

But like many amateur collectors, I don’t know much about the objects I’ve gathered, such as who made them, where they come from, and what stories they tell. They simply spoke to me.

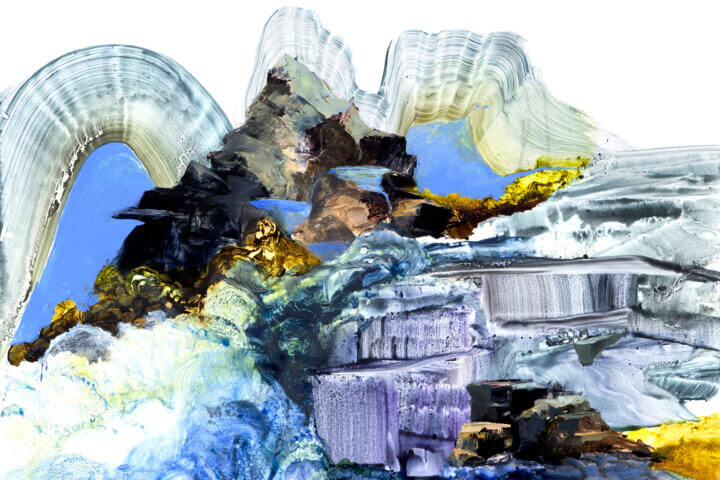

A thought-provoking new exhibit called “What Makes History? New Stories from the Collection” at the Concord Museum invites visitors to think about how and why we collect and keep certain objects and how we make history by doing so.

The eclectic exhibit includes various items, some of which have never been on view, including a selection of fans from around the world. One fan, made in Japan, celebrated our country’s 1875 Centennial. Look closely and spot a tiny image of Concord’s Minute Man monument on it.

There are intricate calling card cases, colorful fireplace bellows created by free Black workers in Acton, and chairs, textiles, clocks, and quilting pieces.

This fireplace bellows was made in Acton in the 1840s. Courtesy photo

Katie Gilmore Reed, some of whose collection of nearly 200 fans are displayed in the exhibit thanks to her granddaughter’s donating them to the museum, was born in the late 1860s and grew up in Concord. She cherished the fans, and when friends came for lunch, she would display them on a table.

“What Makes History?” was put together with the help of Concord Academy students studying local history with their teacher Kim Frederick. They contributed new research and interpretation, and the object labels they produced are posted near the items.

“This has been a really wonderful opportunity to look at these objects with fresh eyes, ask new kinds of questions, interpret them in new ways, and expand their stories,” said Reed Gochberg, associate curator and director of exhibits at the museum.

“We can start to imagine the whole network of people and places involved in creating the items and look at their global origins,” Gochberg said.

Visitors might think of “The Gilded Age” when they view the card cases in the exhibit. Women used them to hold the calling cards they would leave when making social visits to friends or family. Calling cards were common during the Victorian era and were often displayed in decorative receivers (or trays) near the front entry of one’s home.

One of the calling card cases in the exhibit. Courtesy photo

The cases reflect the countless global stories of makers, materials, and places, incorporating materials such as mother-of-pearl, ivory, and tortoiseshell produced in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, according to the Museum, and reflect the techniques used by artists in China, India, and Russia.

The cases in the exhibit are part of a collection belonging to Alice Stanwood Willoughby, an art teacher for decades in Cambridge who likely prized them for their beauty.

It was likely Willoughby’s goal to collect as many styles as possible, but she did not record who made them or where.

In 1952, the year after her death, the 76-item collection was donated to the Concord Antiquarian Society, which later became the Museum.

Of particular interest is a collection of small painted or stenciled fireplace bellows that inspired the exhibit. These “remarkable and beautiful items,” said Gochberg, were produced by women and free Black workers in Acton’s Davis Bellows Factory in the 19th century.

Bellows were common in 19th-century households and were used to help a fire burn. To make them, a wooden top and bottom were joined with folding leather side pieces and a metal nozzle was added. Some examples in the exhibit are swell-top (curved) bellows, reflecting a process that added to their interest — and cost.

The bellows and extra materials and pieces were squirreled away in a building on the former factory site for more than a century until they were moved to a barn in Carlisle, leading viewers to wonder why they were saved and forgotten.

“What Makes History?” runs until August 18. Hours are 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Tuesday to Sunday. For more information, visit info@concordmuseum.org.